Now what?

The number of private universities in India has jumped 47%, from 276 in 2015-16 to 407 in 2020-2021, the latest AISHE data shows[1].

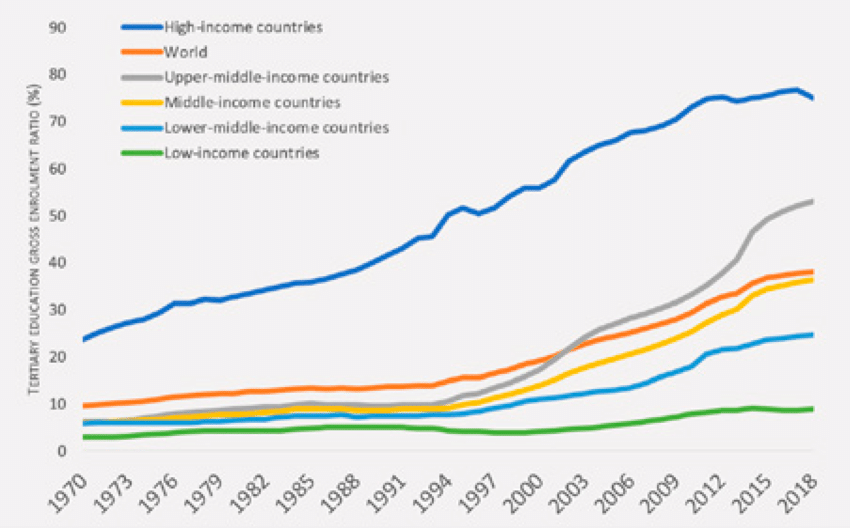

At first, this data does not tell us much if we do not contrast it with other indicators. As per UNESCO’s data[2], India’s gross enrolment ratio (GER)[3] remains low – despite showing a steady increase year by year. It stands at 27% when the world’s GER is around 35% and in high-income countries it has peaked up to 70%. No doubts, India has the potential to substantially increase its GER but how it decides to do it can have a significant impact on the future of the country. Education is one of the most important factors in achieving rapid economic and also technological development.

Therefore, a higher GER for India might accelerate such progress. As the logic goes, if a country expects to increase its gross enrolment ratio, this must come from an increase in the demand for young people to enrol in higher education institutions and, consequently, the supply for higher education degrees must match this increase in the demand.

How is India meeting its increased demand for higher education

The GER trend in India is increasing[4] and the target set by the government is to achieve 50 % GER by 2035[5] so we can only expect this upward trend to consolidate in the upcoming years. But how is this surge in supply for higher education being met? Let us go back to the data. In 2020, the share of government public universities[6] was about 38% across India. This was a decrease from 2012 when the share of state public universities was 46% (Statista). If we contrast this data with the information outlined in the beginning of the article, it does not take much to realise that the demand is being met by an increase in the number of private universities.

In a country where education is still not universal in access, but demand is increasing expeditiously, we are observing a phenomenal growth in the number of private universities – outpacing the other types of universities.

There might be a limit to the capacity of public institutions, incapable of matching the rapid demand for higher education. Private universities seem to be offering a successful formula for the current times, especially in terms of speed and efficiency – easier to enrol, less academic entrance obstacles, variety of degrees offered, locations all over the country… But wait, let’s pause and reflect for a minute. Doesn’t this seem like obtaining a degree is becoming like choosing a car or a travel destination? Where the richest sector of society can access better goods, just because their purchasing power is higher, this being the only factor that counts.

One perhaps should not criminalise private education for the fact that it is costlier than public education – as long as the quality and standards of education are maintained. So, it seems that the transformation of education into a lucrative business is widely accepted in our current societies. We are allowing businesses to operate in the name of imparting knowledge. Nothing wrong with that as far as we are aware of the implications associated with it.

Research has proven that when spending more and consistently in public education income inequality is lowered. On the contrary, higher levels of private education spending are associated with higher wage dispersion and a higher education premium[7] – which in other words means higher income inequality[8].

This is nothing new. Competition in education happens the same way it happens in other sectors: it is fair uniquely when the competitors are of equal strength otherwise it becomes a market failure. In India there is an evident and big gap between rich and poor as per income inequality indicators. So, not only those with higher incomes will unfairly compete and win the race for a private university degree but, on top of that, this race will exacerbate the already existing inequalities.

Marketisation can provide wider opportunities and options to people. When buying this red shirt I am wearing now, I had – at least – 20 options within the same shop, and 20 shops within the same street to opt for. Some people might have chosen a more expensive shop and a fancier shirt, some would opt not to buy a new shirt due to financial constraints, but should we play the same game with education?

By: Celia Gueto Melo

Celia is one of the two EDUREFORM Project Managers. She likes everything that has to do with human welfare. She believes everything is political in a way or another and she just wishes to understand how the world works – as complicated as this might sound.

[1] https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/statistics-new/aishe_eng.pdf

[2] http://data.uis.unesco.org/#

[3] Ratio of people enrolled in higher education institutions to total population of the people in age group of 18 to 23 years,

[4] The GER in India was of 10% in the year 2000. GER in 2021 was 27.1%

[5] New National Education Policy says that the Gross Enrolment Ratio should reach 50 % by the year 2035.

[6] The fees charged for attending university in a public institution is very minimal and is funded for the most part by state governments and the central government.

[7] The earnings ratio between more educated workers and those with less education.

[8] Evelyne Huber, Jacob Gunderson & John D. Stephens (2020) Private education and inequality in the knowledge economy, Policy and Society, 39:2, 171-188, DOI: 10.1080/14494035.2019.163660.

Nisha valvi

A very important topic to ponder upon..